A guide to curing vegetables for storage

Do you have copious harvest? Now keep fresh for months! Proper storage is crucial to ensure that the products remain fresh and retain their nutritional value.

Curning involves placing vegetables in a balmy, droughty and well -ventilated area for a few days, so that their skins get worse and diminutive wounds. This process helps to extend their shelf life and maintain their quality after harvesting.

The following fragment comes from Outside the root basement By Scarce. Has been adapted to the network.

Photo thanks to the kindness of Phil Knapp.

Finding

Hardening is a general term describing additional steps that prepare some vegetables for storage. Most vegetables do not require any hardening before storage. Few that include winter squash and pumpkins, potatoes, sweet potatoes and allium, such as onions, garlic and shallots. The conditions needed for curing and physiological changes are different for each vegetable/group.

In the case of a winter squash and pumpkin, hardening helps to cure the skin, cure wounds, droughty stems and turn their clever into sugars such as sucrose and glucose. (The correct and lively term for this plant tissue connecting the squash and vine is a stalks).

In some climates, winter squash and pumpkins can treat in the field, but in some regions farmers must create the right conditions.

Keeping Squash at 75 to 85 ° F (24 to 29 ° C) and 50 to 70 percent of relative humidity (RH) for a week or two usually ends the curing process and improves their efficiency in long -term storage. (It should be remembered that not all types of squash require hardening, and a separate stage of hardening is not necessary in all climates).

The onion treats the warehouse building in offbeet farm, where it is droughty and balmy, especially on shining days.

Although potatoes and sweet potatoes come from completely different families of plants, physiology behind them is similar. Both crops undergo the sub -encouragement process, A wax protective layer is formed on the skin and wounds.

This layer prevents moisture loss and protects against infection against bacteria and fungi. Joint wisdom says that the skin thickens during the curing process, but in fact the most outer layers of the skin simply attach to the tissue underneath. While potatoes can treat in terms of conditions, the temperature between 54 and 59 ° F (12 and 15 ° C) is the best for speed and preventing pathogen growth. The humidity should be high, of about 80 percent. Sweet potatoes require similar humidity, but much warmer temperatures, ideally from 82 to 86 ° F (28 and 30 ° C).

Garlic and onion, including shallots, can cure after full ripening and enter into sleep.

Sultry and droughty conditions in a few weeks droughty their most outer scales, which become strenuous and flaky. Although they can treat in a wide range of temperatures and humidity, optimal conditions range from about 80 to 90 ° F (27 to 32 ° C) and 50 to 70 percent Rh. Arid outer layers protect onions and garlic from water loss and pathogens. Both in onions and tender garlic, it is also critical that the sewing dries and shrinks during the curing process to prevent pathogens.

When I started, hardening seemed a bit like alchemy.

I read the advice from the University Extension Services, but I did not fully understand the importance of treating success in long -term memory. My first defeat came with onions, which I raised on the winter CSA during the first year of the root basement.

I started them with seeds and carefully cared for them under borrowed lights for growing in the living room of my rented house. (My neighbors and owners definitely thought that I was doing something different.) I planted cuttings and cultivated them all summer, and they grew in beautifully plump bulbs, of which I was proud. If I sold them on the autumn market of farmers, it would end the successful first season.

Instead, I worked their preparations for storage, leaving them too long in the field during a damp fall and not -treated them. This year, my CSA clients received less than half of their onions, because the bulbs grew around the neck and rotten from top to bottom.

Winter Squash almost never treats outside in my farm in Fairbanks in Alaska. Instead, I bring them in the room and but at 80 ° F (27 ° C) and 50 to 60 percent Rh for about a week. Photo thanks to the kindness of Phil Knapp.

In the following years, I learned to collect onions earlier to allow them to droughty more time under the fans in the garage. I was also cautious in rainfall on the onion after the fall of their peaks, I have caution to this day. (My caution may not be completely justified, because other farmers leave the onion in the intermittent rain without a problem after the fall of Tops).

The needs of curing may differ from year to year and from place to place.

I faced the steep learning curves after moving from the upper Michigan peninsula to the inner Alaska and I had to adapt the curing techniques to the modern climate. Winter squash was my biggest challenge related to curing in Alaska.

In Michigan Squash winter and pumpkins usually grew to full maturity for vine – stem stalks (ahem, peduncles), strenuous and wax skins, ground spots and so on – but in Alaska’s tiny season, most winter squash barely overtakes maturity. In addition, the weather during the harvest at the end of August and early September is usually cold and damp. In Michigan I had no problems with the care of a winter squash, neither on the pitch, nor on a droughty and shining deck. In Alaska I have to create these conditions in the room.

Wherever you live and regardless of typical weather designs, you should be prepared for the treatment of crops in the event of need.

This can be particularly tough if you grow many crops that require hardening and treat these crops in different conditions. In practice, it should be determined which spaces are conducive to curing and how different crops can cover their time in these spaces. Additional spaces that can be heated and ventilated as backup copies will assist deal with problems with time or extremely vast harvest.

It is a helpful case that winter squash and pumpkins and Allium are cured in similar conditions. Many breeders exploit the greenhouse to treat these crops, because they have balmy and droughty environments for both. Heated shops and sheds can also work for onions, garlic and squash. Most farmers I know, grow sweet potatoes, also exploit storage space for the curing period, which eliminates additional stages of service between field and storage. Potato stain pads often treat potatoes in ambient conditions (in other words without manipulating temperature or humidity) or in the space for storing potatoes, like sweet potatoes.

You also need to plan hardening configurations and equipment.

The air flow is crucial for all treatment. Still liquid air removes and spreads moisture, maintains even the temperature and prevents the accumulation of gases such as carbon dioxide and ethylene. Remember this when you choose containers or platforms for curing. I once made a mistake, treating a winter squash on plywood shelves. Thanks to impermeable plywood and inappropriate fans, humidity was created under my cabine and I had trouble with rot on their bottom.

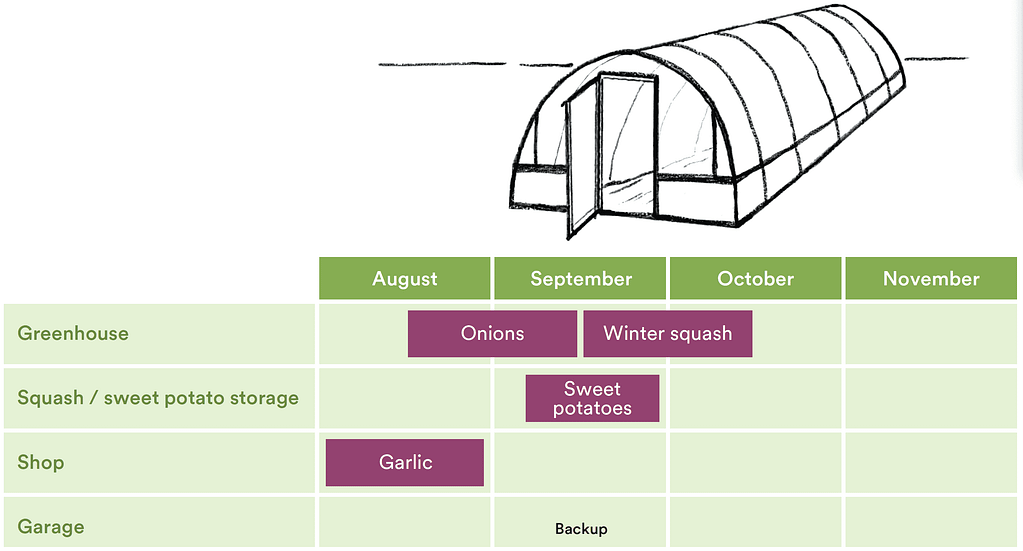

This farm stores sweet potatoes and winter squash in the same room, but because of their different needs,

He doesn’t cure them together. They treat sweet potatoes in stock (where it is easier to maintain stability

Temps and humidity), and winter squash combine sweet potatoes after curing in a greenhouse. They also treat

Onion in a greenhouse before the winter squash. The farm treats garlic in the store building and has a garage

Available as backups in the case of bumper growing or a problem with one of the other spaces.

Many farms, especially in diminutive scales, treat Allium and Squash in individual layers on teams or tables to maximize the air flow across and under crops. Some larger farms treat their onions and squash in loose containers, individually or in stacks. The trick here is to place fans on containers, lying flat and directed up, pull up the air up; It is almost always easier to pull than to push the air. If the fans above the baskets are not forceful enough, you can improve airflow in stacks, wrapping external, creating makeshift chimneys.

Farms that store things such as potatoes and onions in a loose pile, often exploit perforated pipes or culverts in piles of ventilation. As in the case of aeration compost, ventilation pipes provide fresh air to the bottom with loose piles to keep the temperature more effectively and control moisture.

How much ventilation is enough?

Basically, the air should be moved, though subtly, in each place in a stack, stack or container on brewing vegetables. With your hand you can feel the air movement under or through piles or piles of vegetables. If you are not sure, you can also exploit smoke or dust to observe a subtle air movement.

Observing how smoke moves – for example, through the bottom of the pile of volume containers – you know that the air actively moves through hardening crops. If there is not enough air flow, add more or larger fans.