Vermicast Constructions: Worm Real Estate

Farmers rely on earthworms to create vermicomposting systems, and the place where the earthworms live and grow is the most critical part of the operation. Adding vermicompost improves seed germination, increases seedling growth and increases plant productivity. So if you’re ready to get started with vermicomposting, read on!

Below is an excerpt from Worm Farmer’s Handbook By Rhonda ShermanIt has been adapted to the web.

Types of Vermicomposting Systems

Let’s look at the main types of vermicomposting systems that worm farmers utilize to raise worms and produce vermicompost. I start with the simplest one – the chute – and then cover pits, bins and continuous flow containers.

The shafts

Windrows are linear heaps containing mulch and raw materials that will eventually reach a height of 24 to 30 inches (61–76 cm). They are typically 4 to 8 feet (1.2–2.4 m) wide and as long as space allows. Many people living in milder climates, such as the West Coast of the United States, have created windrows outdoors for vermicate production, although windrows can also be set up inside enormous buildings.

This shade house at Arizona Worm Farm houses a dozen wedge-shaped vermicomposting piles. Photo courtesy of Zachary Brooks.

A front-end loader, wheel loader, shovel, or fork can be used to make a windrow. Simply spread a 6- to 8-inch-deep (15-20 cm) layer of mulch of the desired width and length on the bare soil and add 1 pound (0.5 kg) of Eisenia fetida worms per square foot (0.09 m2) of surface area. It is critical to first smother the vegetation so that grass and weeds do not grow into the windrow, which could interfere with the harvest. Because composting worms do not burrow, you do not have to worry about them moving out of the windrow into the soil. After the worms have settled into the mulch, apply the material in a layer 1 to 11⁄2 inches (2.5-3.8 cm) deep and wait until the feed has been eaten before adding more. In frosty weather, 3 to 4 inches (7.6–10.2 cm) of material can be added to the top of the pile to aid keep the worms heated. Although many worm farmers have success with outdoor piles, some report problems with excess moisture, anaerobic areas, and predators such as moles and birds. Vermicomposting in piles is a leisurely process that can take up to 12 months to produce finished vermicompost.

Pits or ditches

Pits or trenches have been used for decades. Like other vermicomposting systems, you spread out damp mulch, add worms, and spread gaunt layers of the material on top. People like vermicomposting pits because they are plain holes in the ground—no construction required. The clay sides provide insulation from both heated and chilly weather. Some people choose to line their pits with cement blocks. However, raising worms in pits can strain your back from bending over so much. Another drawback is that pits can flood in weighty rains.

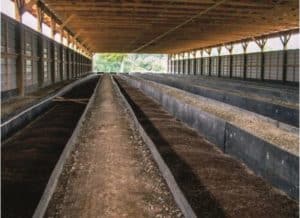

Earthworms feed on pig manure in shadowy ditches inside this enclosure at a North Carolina hog farm.

In the early 21st century, a successful trench model was developed in North Carolina. Tom Christenberry, a hog manure vermicompostor, was having problems with his flow-through bins overheating, so he created a trench system that allowed the earth to moderate excessively low or high temperatures. Inside the barn, he dug five trenches 4 ft wide, 200 ft long, and 21 in deep (1.2 × 61.0 × 0.5 m) from poles. Between the trenches were packed dirt and gravel paths that could support a tractor. To feed the earthworms, he drove the tractor straddling the trench. The tractor pulled a manure spreader calibrated to spread hog manure into the trench, and then the worker used a rake to evenly spread the manure to a depth of 1 inch (2.5 cm). The feeding process was carried out weekly using raw pig manure washed from the barn and passed through a solids separator.

Before you decide to install a pit system, consider whether you can handle all the bending that will be required to feed, check worms and soil conditions, and harvest the vermicompost. I used to think I could work with pit systems, but now I realize I can’t handle kneeling, bending, and reaching into the pit on a regular basis.

Baskets

Worm bins are a type of containment system that can be built, purchased, or reused. They are installed much like the previously described systems—with damp litter on the bottom, worms added to the top, and then the feed added in gaunt layers on top of the litter.

Concrete container for earthworms on a farm in the Dominican Republic.

To make worm bins, worm farmers often reuse discarded items, including refrigerators, animal tanks, bathtubs, barrels, wooden or plastic boxes, mortar trays, plastic buckets, washing machine tubs, and other containers. If such bins have solid bottoms or sides, drill holes for drainage and air flow.

Worm beds and containers can be built by hand from a variety of materials, including wood, plywood, concrete or cinder blocks, fiberglass, structural clay roofing tiles, poured concrete, or brick. Wood is one of the most popular materials, but untreated wood can decompose in 4 to 10 years, depending on climate and other factors, so many people cover it with plastic or coat it with untreated linseed oil. Avoid using redwood, cedar, or other aromatic woods for containers; they contain tannic acid and resinous sap that are harmful to earthworms.

Worm farmers around the world build concrete bins, often on bare ground. They are inexpensive, simple to obtain, and will not rot. Concrete also provides better insulation than plywood, so it will keep your worm bed warmer in winter and cooler in summer.

Remember that birds love to eat worms, so if your containers are not covered, you should utilize netting to keep out bird predators. Also, always protect the worms from direct sunlight by placing the containers in a well-shaded area, placing them under a roof, or covering them with lids.

These MacroBins for vermicomposting at the San Diego composting facility are the same ones I utilize at my composting facility in North Carolina.

The worms in my Worm Barn in the Compost Learning Lab live in two MacroBins. These bins are made by Macro Plastics for storing and transporting vegetables. When I first saw one, I immediately thought, “That would be a good worm bin!” and decided I had to buy one. The MacroBin is made of high-impact copolymers and has glossy surfaces and vents on all sides and the bottom. It is approximately 45 inches long, 48 inches wide, and 34 inches high on the outside (1.1 m x 1.2 m x 0.9 m). The inside of the bin is approximately 41 inches by 45 inches by 29 inches (1.0 m x 1.1 m x 0.7 m). It can hold 1,300 pounds (590 kg) of material and can be lifted by a forklift from either side. The MacroBin sells for about $230, with discounts for bulk purchases. I didn’t know anyone else was using these farm bins as worm bins until I saw 10 of them prepared for vermicomposting while touring a composting facility in San Diego!

Garry Lipscomb and Bill Corey, owners of NewSoil Vermiculture LLC in Durham, North Carolina, made the containers from 55-gallon (210 L) plastic drums for their commercial operation in the basement of their home.

Many worm farmers reuse plastic IBCs (intermediate body containers) to make worm bins. These are enormous tanks used to store and transport 275–330 gallons (1,040–1,250 l) of liquid or bulk materials. Novel IBCs cost less than $150, with versions housed in metal cages available for about $100 more. These tanks are reused for a variety of purposes, so it is fairly simple to buy them used at a lower price.