Eliot Coleman’s Guide to Perfect Compost

Compost is key to a lush, copious garden. Do you know how to turn kitchen scraps and garden waste into perfumed, crumbly plant food?

If not, your garden is losing a lot and You you are missing out on one of the most fascinating and crucial lessons that organic gardening can teach you: the straightforward fact that in the cycle of life, all waste is food.

Learn the basics of compost making from year-round gardening expert Eliot Coleman and discover the up-to-date joy of growing your own food.

Below is an excerpt from Harvest all year round: organic vegetables from your garden all year round By Elliot ColemanIt has been adapted to the web.

Fertile soil is key to growing garden vegetables

So often the obvious solution is within reach, but it looks so straightforward that we don’t notice it. Generations of gardeners have consistently come up with the same logic: fertile soil is the key to growing garden vegetables; compost is the key to fertile soil. The first step in four-season harvesting is learning how to make good compost. It’s not tough. Compost wants to happen.

Compost is the end result of the decomposition of organic matter. It is essentially a brownish-black crumbly material that looks like a affluent chocolate fudge cake. Compost is created by managing the decomposition of organic matter in a pile called a compost pile. Compost increases soil fertility because the fertile soil and compost share a vast population of organisms that feed on the decomposing organic matter. The life processes of these organisms lend a hand make the nutrients from the organic matter and the minerals in the soil available to growing plants.

Fertile soil is full of life. Compost is salvation.

Gardeners are not alone in their reverence for compost. Poets find it equally inspiring. Andrew Hudgins, in his poem “Compost: An Ode,” refers to the compost pile’s role in uniting life and death: “the tranquil sinking of a thing into its possibilities.” John Updike reminds us that because “all processes are reprocessing,” the forest can consume its fallen trees, and “the carcass of the groundhog disappears, leaving a poem behind.” Walt Whitman marvels at how composting allows the earth to grow “such sweet things from such corruption.”

Good compost, like any carefully crafted product, is not a product of chance. It is created through a process involving microorganisms, organic matter, air, moisture, and time that can be arranged in anyone’s backyard. No machinery is needed, and no moving parts need repairing. All you have to do is arrange the ingredients according to the specifications in the next section and let nature’s decomposers do the work.

Compost Ingredients

The ingredients in compost are the organic waste products produced in most yards, gardens and kitchens. That’s what’s so wonderful and fascinating about compost. If you collect organic waste, it eventually breaks down into compost. There’s nothing to buy, nothing to ship, nothing exotic. This acknowledged “best” garden fertilizer is so in tune with the cyclical systems of the natural world that it’s made for free in your yard from naturally available waste products.

The more eclectic the list of ingredients, the better the compost. It makes sense. The plant waste that goes into your compost was once a plant that grew because it was able to absorb the nutrients it needed. So don’t leave out any weeds, shrub clippings, cow patties, or odd leaves you might find. If you mix in a wide range of plants with different mineral compositions, the resulting compost will cover the spectrum of nutrients.

I suggest dividing your compost into two categories based on age and composition. These two categories are called green and brown.

Green matter consists mainly of youthful, soggy, and fresh materials. They are the most dynamic decomposers. Examples include kitchen waste such as apple peels, scraps, carrot tops, and bread, and yard waste such as grass clippings, weeds, fresh pea shoots, outer cabbage leaves, and dead squirrels. The average home and yard produce such waste in surprising amounts. National solid waste data indicate that about 25 percent of household waste consists of food scraps and yard waste.

Brown ingredients are usually older and drier than green ingredients, and they also break down more slowly. Examples include dried grass stalks, ancient corn stalks, dried pea and bean shoots, reeds, and ancient hay. The brown category is usually underrepresented in the average garden. To start, you may want to buy straw, the best brown ingredient of all. Straw is the stalk that supports the amber waves of grain in crops such as wheat, oats, barley, and rye. After the grain-bearing ears are harvested, the straw is baled as a byproduct. You can buy straw in a few bales at a time from feed stores, stables, or a good garden supply store.

The advantage of straw as a brown ingredient is that it almost guarantees the success of your composting efforts. When home gardeners encounter stinking failures in their attempts to make good compost, the culprit usually lies in the lack of a suitable brown ingredient. In the years to come, as you become an expert composter, you may decide to expand your repertoire beyond this beginner’s technique, but this is the most reliable method for beginners or experts.

Building a composter

Choose a spot near your garden so that finished compost is close at hand. If possible, place the pile under the branches of a deciduous tree to provide shade on balmy days and for the sun to thaw the pile in spring. A spot near the kitchen makes it straightforward to add kitchen scraps. Access to a hose is useful for times when the pile needs extra moisture. If the location is higher than the garden, the demanding work of wheeling loads of compost will have gravity on its side.

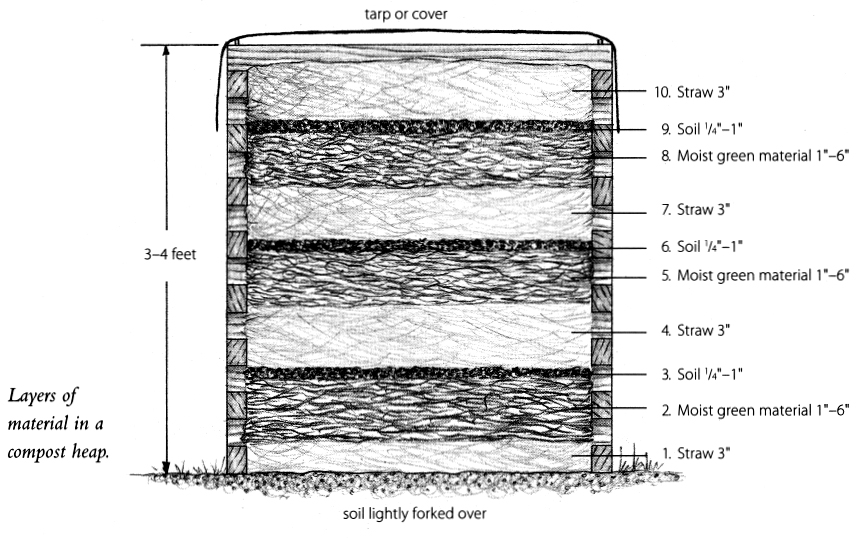

Build a compost pile by alternating layers of brown ingredients with layers of greens. Start with a layer of straw about 3 inches deep, then add 1 to 6 inches of green ingredients, another 3 inches of straw, then more green ingredients. The thickness of the green layer depends on the type of materials. Loose, open material, such as green bean shoots or tomato stems, can be applied in a thicker (6-inch) layer, while denser material that tends to stick together, such as kitchen scraps or grass clippings, should be applied in gaunt layers (1 to 2 inches). These thicknesses are a starting point, but you’ll learn to adjust them as conditions require.

Sprinkle each green layer with a gaunt layer of soil.

Make the soil about 1/2 inch deep, depending on what kind of green material is available. If you have just added a layer of weeds with soil on their roots, you can skip covering that layer with soil. Adding soil to the compost has both a physical and a microbiological effect: physical, because some soil components (clay particles and minerals) have been shown to aid in the decomposition of organic matter; microbiological, because the soil contains millions of microorganisms that are needed to break down the organic matter in the pile. These bacteria, fungi, and other organisms thrive in the hot, soggy conditions when decomposition begins.

If your garden is very sandy or gravelly, you may want to find some clay to add to the mound as topsoil. As an added benefit, the clay will improve the particle size balance of the soil in your garden.